Why you need to know the difference between leading and lagging economic indicators

But at the same time, the unemployment rate remains very low, lots of Australians seem to be holidaying in Europe and restaurants and cafes are doing well. While perplexing, it’s not that unusual at turning points in the economy for various indicators to be conflicting.

Leading versus lagging economic indicators

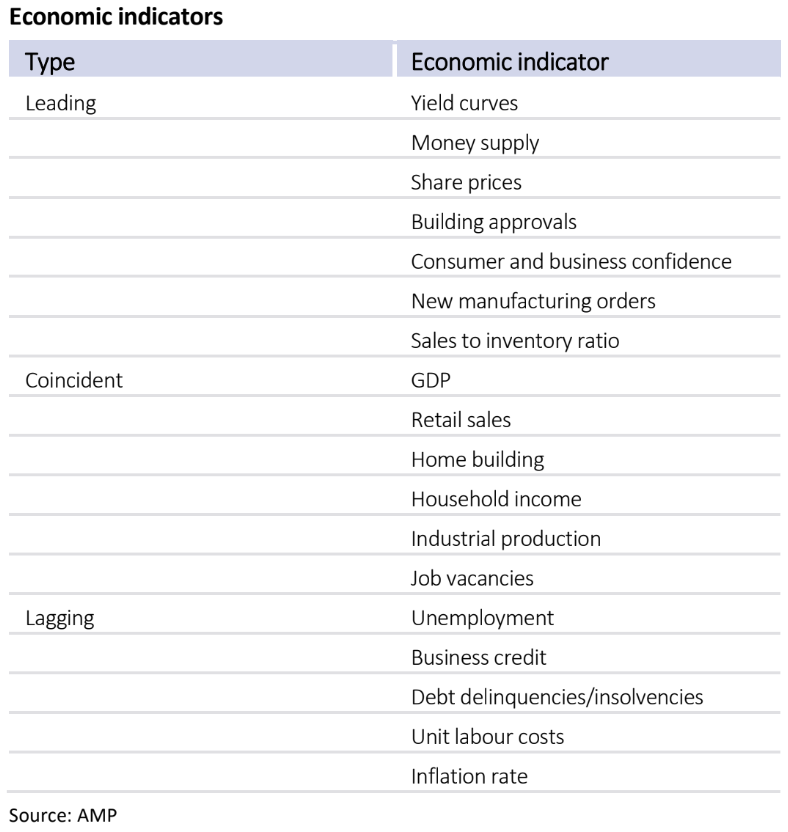

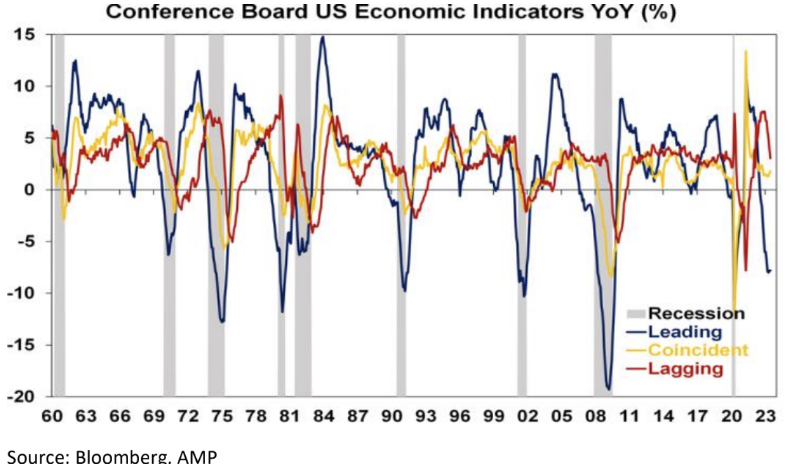

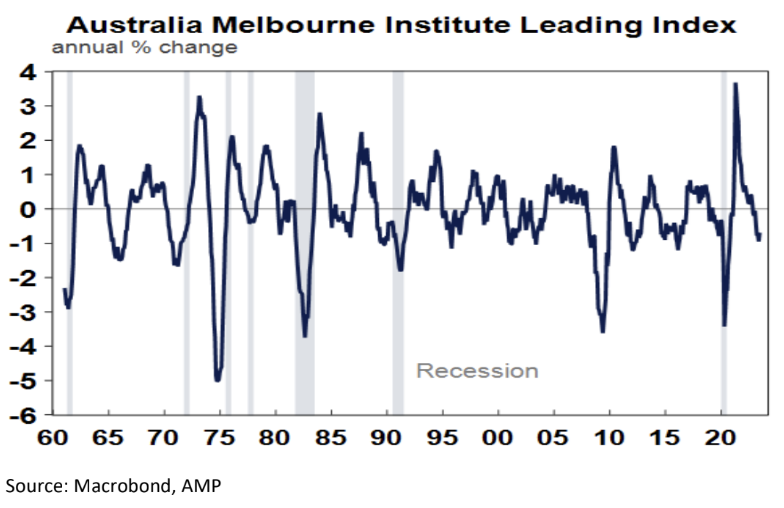

- Leading economic indicators are economic indicators which lead the economic cycle often by 6-18 months. This is because they reflect changes in monetary policy – like the yield curve which is the gap between long term bond yields and short-term interest rates which are a guide to whether monetary policy is tight or loose and money supply growth - or they respond quickly to changes in interest rates – like share markets, confidence and building approvals.

- Coincident indicators move with the economic cycle, so GDP growth by definition is coincident as are retail sales and household income.

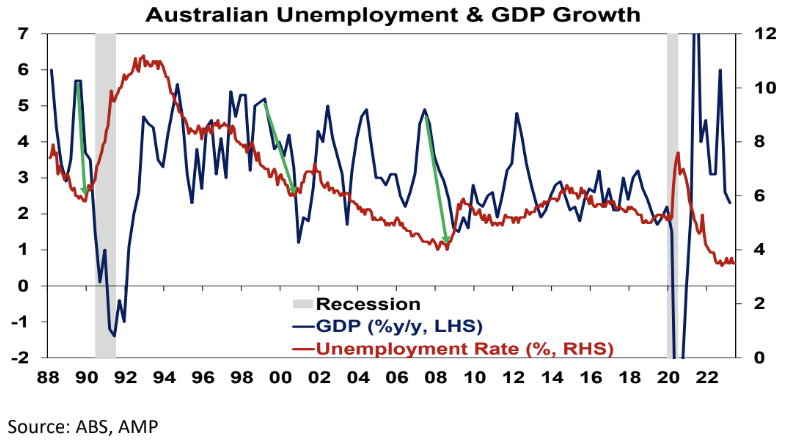

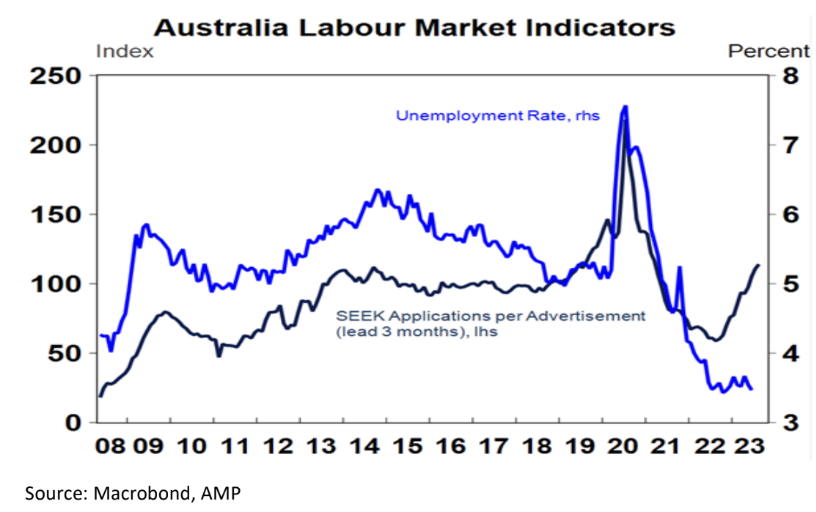

- Lagging indicators tend to turn after the economic cycle has turned. Unemployment and inflation are lagging indicators because companies are invariably slow to adjust hiring and pricing decisions. They persist with decisions to hire or raise prices after demand has slowed because it takes a while to recognise that any downturn is permanent and turn around the mechanisms by which they hire and raise prices.

Current conditions

This is particularly relevant now in relation to unemployment and inflation.

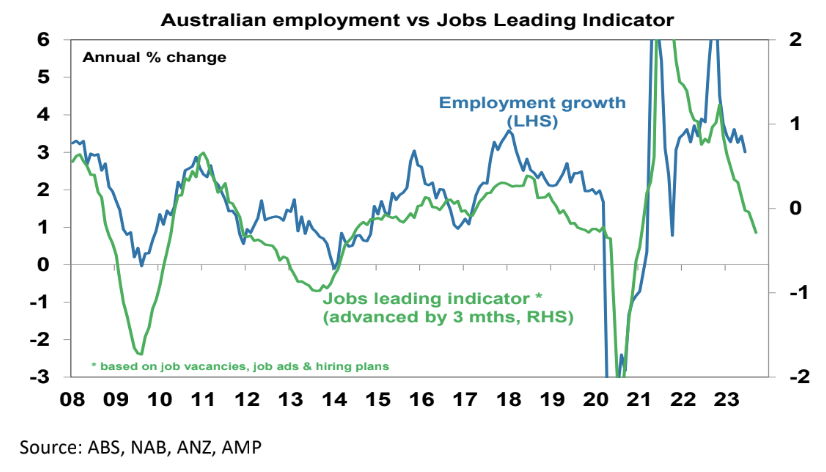

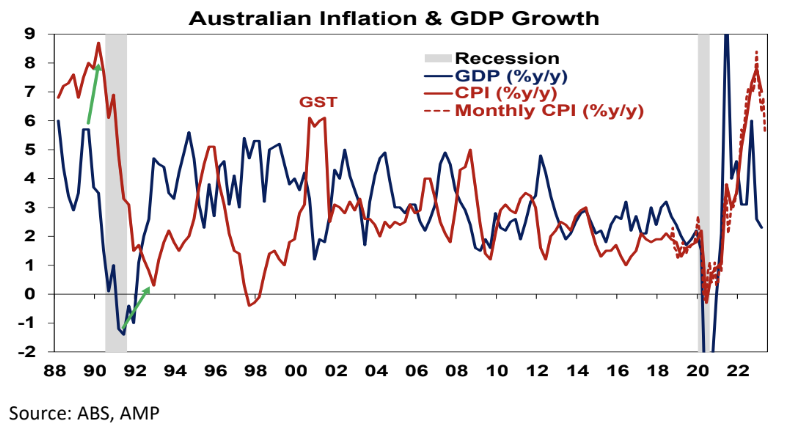

Jobs leading indicators are pointing down

The pandemic also distorted normal economic relationships. However, as can be seen in the next chart significant swings in unemployment around the early 1990s recession and the early 2000s and 2008 growth slowdowns saw unemployment tend to lag swings in GDP growth (eg, see the green arrows). This was particularly evident around the early 1990s recession with unemployment still going down as GDP slowed in 1989 and only starting to rise in earnest once the economy was in recession. After the recession ended in mid-1991, unemployment did not peak until late 1992.

Our leading indicator of jobs growth - based on vacancies and hiring plans - points to a sharp slowing in jobs growth ahead.

Inflation also lags

Of course, the pandemic distorted things pushing inflation down very quickly in 2020 and the combination of pandemic-related distortions, floods and the war in Ukraine which depressed supply helped boost inflation since 2021 but the supply side is now normalising.

Concluding comment

- Still low unemployment and still high inflation are not that unusual despite slowing growth because they both normally lag big swings in the economic cycle – running the economy with too much focus on them is a bit like driving a car with the rear-view mirror.

- As such the RBA and other central banks need to tread carefully from here and allow for the lags from the rapid rise in interest rates to work through lest they end up pushing unemployment far higher than they need to in order to return inflation to target. Fortunately, the minutes from the last RBA board meeting suggests it’s aware of the risks.

We also covered this subject on the most recent edition of Livewire's Signal or Noise. To hear a verbal explanation click to watch the video here:

2 topics