Why the RBA won't follow the Federal Reserve (and what it means for your money)

Something remarkable occurred among Western central banks throughout 2022 and 2023. More or less, they all followed the Federal Reserve and hiked interest rates in unison. Around the world, consumers and investors were dealt the harshest rate hiking cycle in more than 40 years, shaving US$30 trillion off global stock and bond market values in the process.

At that time, the "all together" move made sense. Everyone was facing the same inflation shock, everyone was facing the same supply chain difficulties, and asset markets in most major economies were reacting the same way to both.

And now, once again in 2024, everyone is waiting for the same cue. When the Federal Reserve cuts rates, other central banks will follow right afterwards... right? Not necessarily.

This wire will aim to explain why central banks may all move interest rates at different times as this part of the cycle takes shape - a phenomenon that economists call "decorrelation" - with the help of Chris Siniakov, Managing Director, Fixed Income at Franklin Templeton. Siniakov works closely with Andrew Canobi, who wrote the piece that inspired this one.

Is it true that everyone just follows the Fed...and is the RBA always late?

There is some truth to the old adage "When America sneezes, the world catches a cold", but Siniakov argues that the correlation between the RBA and the Fed is not one-for-one.

"The global economy is heavily intertwined across regions and countries through multiple linkages such as manufacturing value chains, capital flows, exchange rates, etc. So, it should not come as a surprise if the correlation across central banks is high, but the devil is always in the detail," he says.

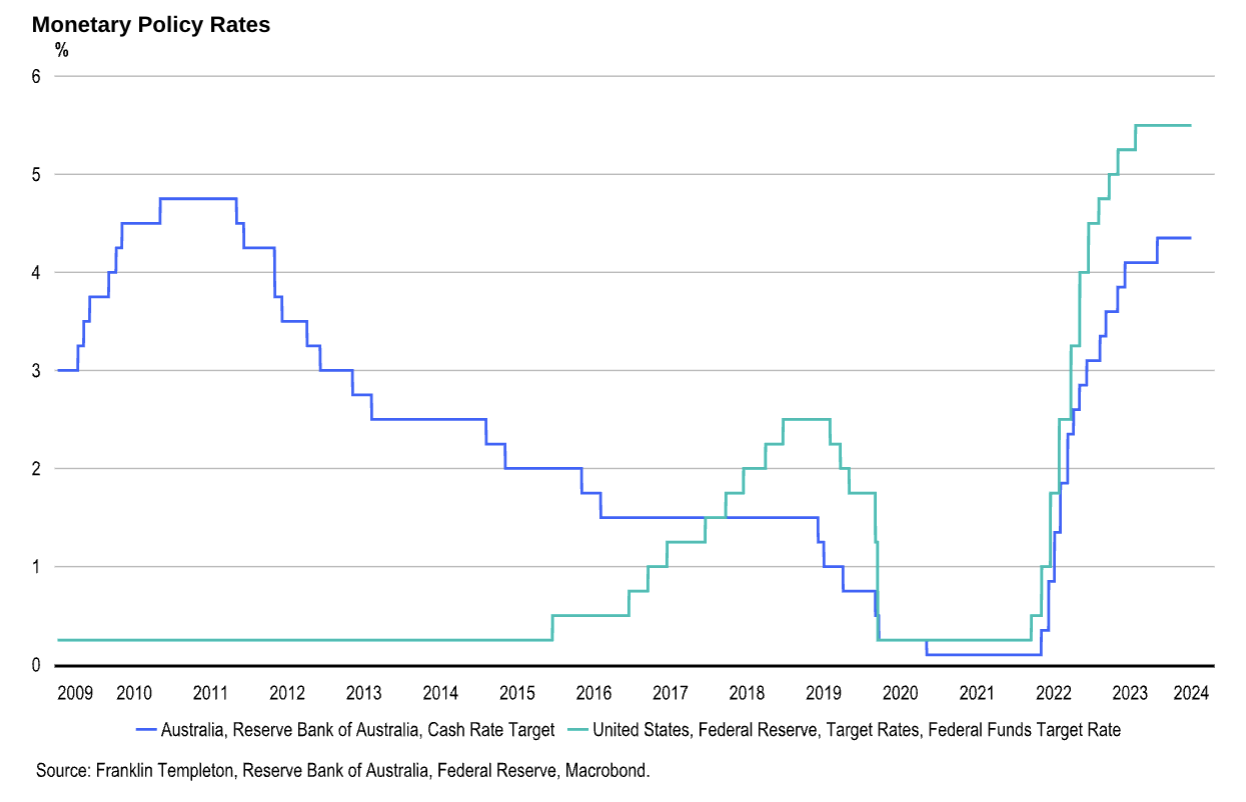

In fact, since the Global Financial Crisis (and certainly in the current cycle we are in), the Australian cash rate and the US cash rate have often moved at different speeds and at different times. The following chart shows this:

"Longer term policy behaviour in Australia has differed from global peers like the US and it will again in the not-too-distant future," Siniakov adds.

Why is there suddenly a lot of talk about central banks choosing their own path?

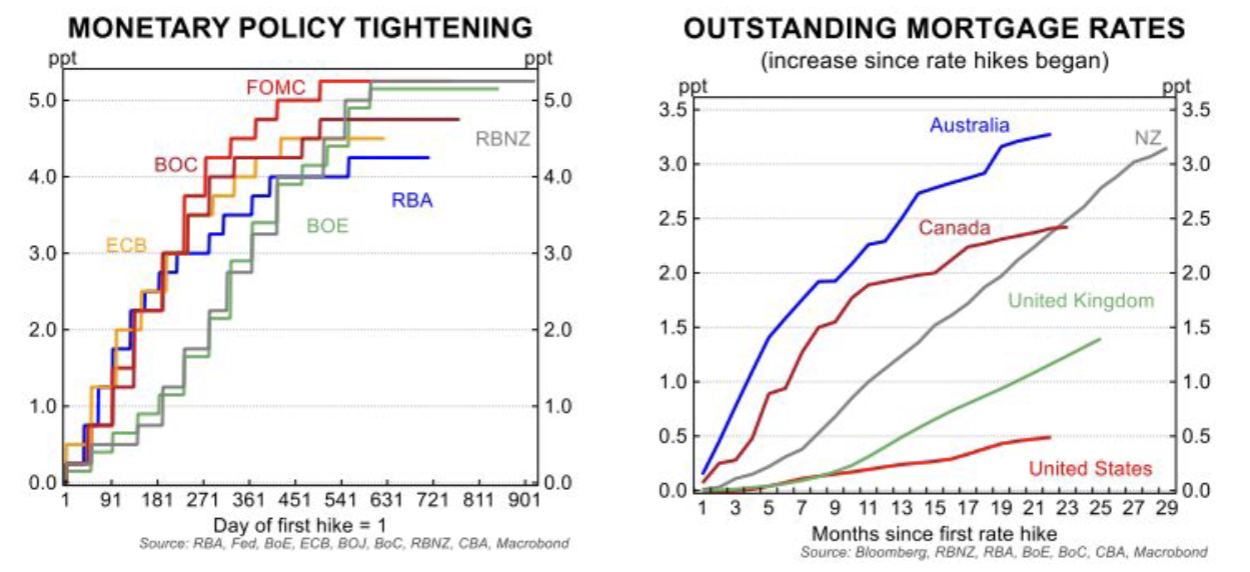

To answer this question, Siniakov uses the following two charts from the CBA Economics team. They show the impact of monetary policy movements against mortgage rates in the major economies.

"The RBA increased the cash rate by 4.25%, which happens to be the lowest increase amongst this pack (left chart). But, when you look at the pass-through to mortgage rates (right chart), Australia has delivered the largest impact on household mortgages and earlier than other economies," Siniakov notes.

"At the other end of the spectrum, the US has raised policy rates the most (along with our friends across the ditch) but the impact on mortgage rates is significantly less in the US due to the nature of its longer (30yr) fixed rate mortgage market."

"The result is that Australian household consumption has collapsed versus still robust US consumption. Now overlay government fiscal policy, labour market structures, immigration policies, housing markets, unique CPI baskets, et cetera and it's clear to me that central banks will walk their own path as this cycle plays through more fully," he adds.

What are different Livewire contributors saying?

Finally, I thought it would be pertinent to compile some of the other views in the interest rate discussion. It's been very revealing seeing how different fund managers who work in different asset classes are thinking about the rate cut profile moving forward.

For instance, Payton Capital's Craig Schloeffel believes that there will be "two to three" RBA cuts in 2024. Chris Bedingfield from Quay Global Investors went one step further, arguing that without changes at the fiscal level, the march back to a zero interest rate environment in Australia "may take three to five years" but added, "This march feels inevitable". Both Bedingfield and Schloeffel work in and around the Australian residential real estate market.

At the other end of the spectrum, some, like Coolabah Capital's Christopher Joye, think the RBA should never have finished hiking rates so early. Speaking on The Rules of Investing recently, Joye argued that "no one understands why Australia's cash rate is 4.35% when normally, it would be 1.5% above the US Fed Funds rate." Such a scenario would imply an Australian benchmark interest rate of above 6.5%.

Some participants believe the RBA won't be able to afford to cut this year. For instance, Dion Hershan, Yarra Capital Management's Head of Australian Equities, told Livewire that Australia's economic resilience and high asset prices mean the RBA will not cut rates this year. Challenger Chief Economist (and former RBA boffin) Jonathan Kearns agrees, arguing recently that rate cuts are "by no means" locked in for calendar 2024. Rates markets, as of writing, are now priced in this last camp - the RBA won't cut until February 2025, with a second full cut not even in the picture.

So why is there such a divergence among market participants who work in the same market, and see the same data as the central bank would see?

"Behavioural finance tells us that investors are not always rational. People make decisions that are influenced by emotion (fear and greed) versus facts and figures. Overconfidence can creep in. Loss aversion. Herding mentality. Cognitive biases. Students of economics also work to different timeframes and therefore interpret the same data for their specific horizon and purpose. At the end of the day, all of this presents an opportunity for active managers," Siniakov argues.

.png)

3 topics

1 fund mentioned

7 contributors mentioned